Early Years

You grew up in a creative family. How did this environment shape your early relationship with art?

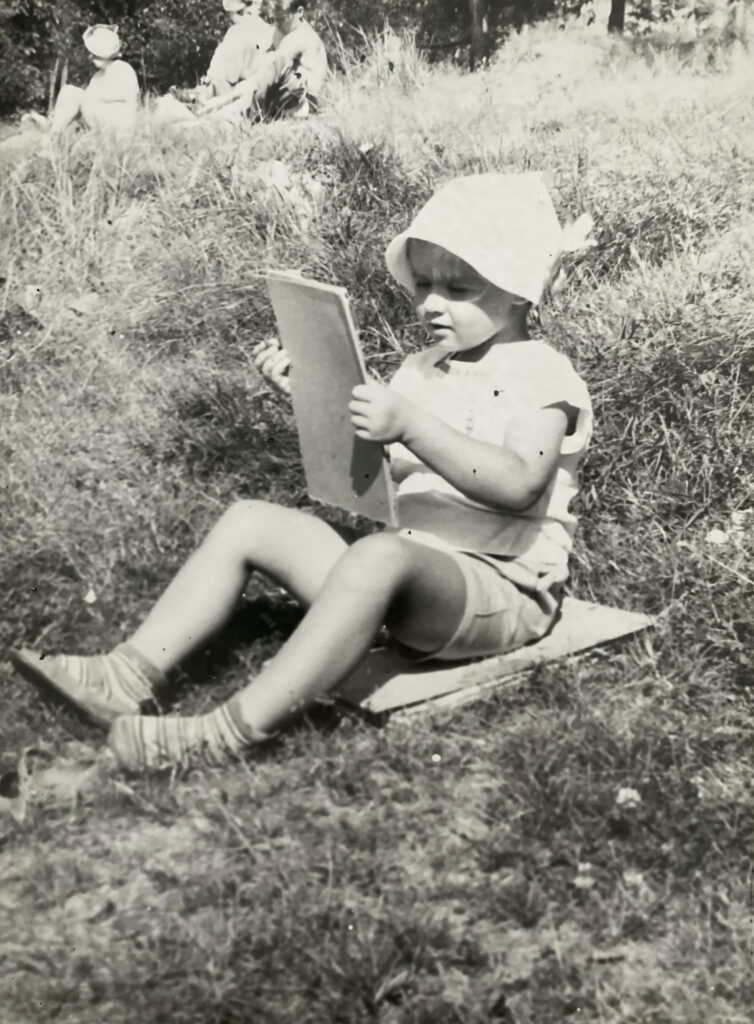

Olga Survillo: From a very early age, I understood that making art is an essential part of human life. Paper, pencils and paints were always within reach on my father’s desk; Indian ink, celluloid and rapidograph pens on my mother’s. We went to exhibitions together. The guests, mostly my parents’ colleagues and artist friends, gathered in our home to discuss new book illustrations and filmstrips. My father sometimes took me to the television studios where he worked, during the exciting period when children’s programming was just being launched.

Your father, Raymond, was a professional artist. In what way did he introduce you to the idea of design as a disciplined, production-oriented practice?

OS: Moving a brush across paper was, even in childhood, an act of responsibility. Printing an etching is a complex technical process that requires knowledge and experience. I learned early that creativity is not only a burst of inspiration; it is also accumulated skill, perseverance, and a consistent effort aimed at bringing an idea into material form.

What role did your mother, Nina, play in the development of your artistic sensibility, particularly through her work on archaeological expeditions?

OS: While my father always praised my efforts, my mother was more critical; we argued, and that tension was enormously helpful. Through her, I entered the world of expeditions, scholars, historians and archaeologists. I handled artefacts left by people who lived thousands of years ago: jewellery, nails, horse harnesses, shards of pottery. My mother drew everything the archaeologists unearthed. I had an opportunity to understand that the houses of the ancients were radically different from ours. As a teenager, I made reconstructions of dwellings and floor plans. It was an immense broadening of horizons.

How has that experience continued to influence your visual language?

OS: Beyond the digs themselves, I loved travelling through villages and provincial towns, mostly in central Russia, observing rural life, churches and monasteries. The people we met were remarkable, deeply knowledgeable about architecture. That experience later proved invaluable in my work in cinema. Equally important were the objects we excavated; many were masterpieces of ancient craftsmanship. Their extraordinary skill shaped my own sense of responsibility toward the craft I practice.

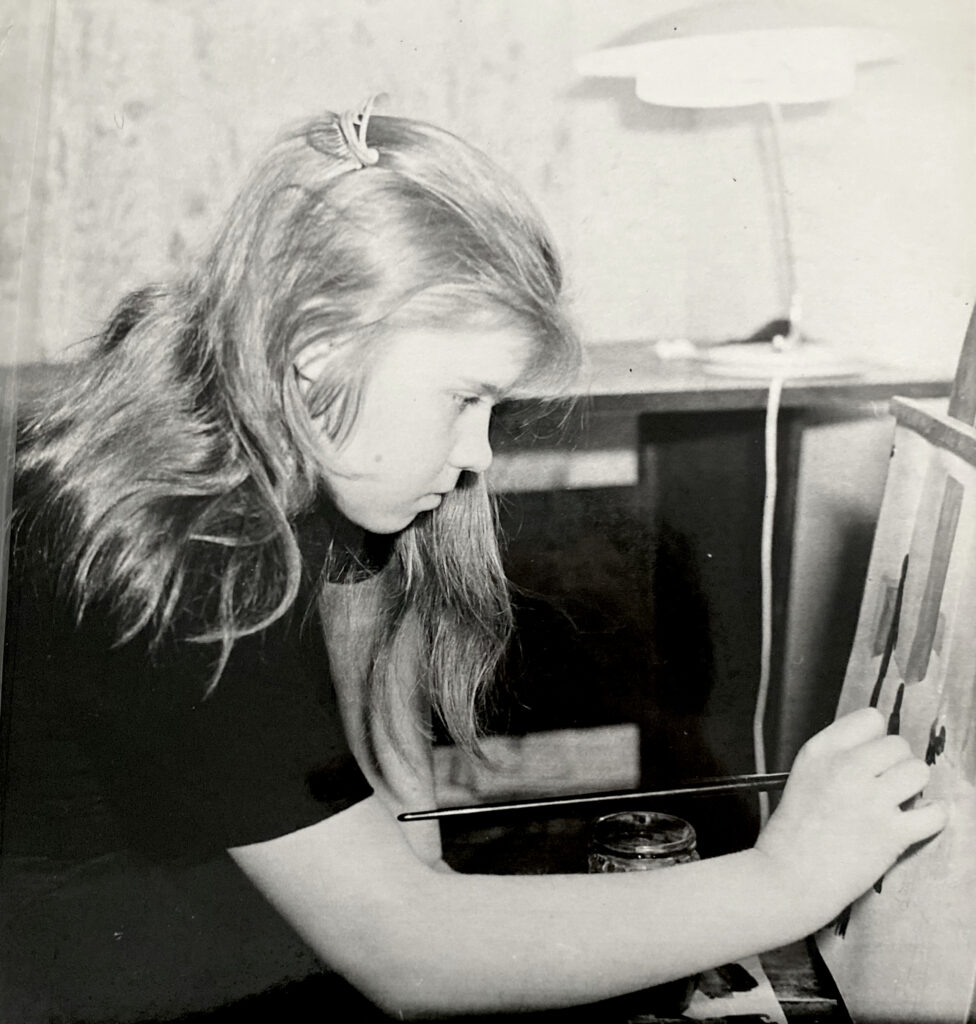

What drew you to the Moscow Secondary Art School, and what were the most important lessons you took away?

OS: Above all, the company of people who shared the same passions and had grown up in similar environments. I discovered that watercolour could be painted in countless ways; each teacher was brilliant in a different manner. One encouraged broad, wet-into-wet washes on glass, letting colours bleed and float; another insisted on precise, dry, detailed observation. Everything was displayed and discussed passionately during crits. The same variety existed in oil painting classes: some studios produced enormous canvases, others exquisite miniatures on small panels. Formalism was not encouraged, but the main emphasis was on deep understanding and mastery of materials and techniques; an absolutely crucial experience. We also had daily four-hour life-drawing sessions (still life, portrait, figure), composition classes and summer plein-air programmes in Kyiv and Vilnius. I remember that time with great warmth; it was a genuine education in professionalism.